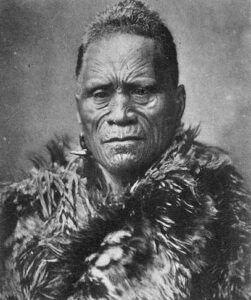

Parematta Māori / Te Kotahitanga

This article reproduced below was first published on the Newsroom website. The version below is illustrated and contains links to additional information of interest.

However, plse click here if you’d like to see the Newsroom published version: https://newsroom.co.nz/2024/07/04/could-a-maori-parliament-arise-again/

A New Māori Parliament?

Te Pāti Māori has issued a declaration – Te Ngākau o Te Iwi Māori – to establish an autonomous Parliament for Māori. This call follows the government’s continuing hostility to Māori.

Te Pāti Māori has issued a declaration – Te Ngākau o Te Iwi Māori – to establish an autonomous Parliament for Māori. This call follows the government’s continuing hostility to Māori.

‘We now begin the process of establishing our own Parliament’ says co-leader Debbie Ngawera-Packer (Ngāti Ruanui). Anchored in tikanga, and focused on future generations, the new Māori Parliament will advance the ‘transforming of Aotearoa’ into a nation respecting the te tino rangatiratanga of Māori, and of all peoples. This may be a new policy for Te Pāti Māori. But it’s also a recurring theme in our nation’s political history; sadly, Māori have been here before, many times.

Continuing Customary Autonomy for Māori

From the very beginning, Māori have sought some form of national political autonomy. Early Governors resisted, instead conceding lesser degrees of self-rule to scattered iwi, via Native Exemption legislation. Pākehā settlers were alarmed, demanding that tribal structures be dismantled as a means of acquiring land.

In 1845, Governor Grey quickly abolished what concessions existed, insisting that, despite Treaty assurances to the contrary, only the Crown could exercise political authority. This decree that would resonate through our history, giving rise to warfare, iniquitous legislation, Māori dispossession and political marginalization.

In 1845, Governor Grey quickly abolished what concessions existed, insisting that, despite Treaty assurances to the contrary, only the Crown could exercise political authority. This decree that would resonate through our history, giving rise to warfare, iniquitous legislation, Māori dispossession and political marginalization.

In a fine ironic twist, it was Debbie Ngawera-Packer’s tūpuna who called the first Māori gathering to propose Māori political unity. The April 1854 hui was held at Manawapou, in South Taranaki, called by Ngāti Ruanui to dedicate new wharenui at Ketemarae, and Manawapou. Māori from Taranaki and far beyond attended, promptly expressing tribal unity in resistance to continuing land losses. A recent 1852 New Zealand Constitution had also denied Māori the franchise.

Attending the hui was Tamihana Te Rauparaha, a young Christian rangatira who had been to England, observing royal authority firsthand. Tamihana would later persuade Te Wherowhero of Waikato to accept a distinct form of Māori kingship. Rangatira from all over Aotearoa came to Ngāruawāhia in 1858, to confer the mantle of Māori King on Te Wherowhero, symbolically laying their lands and service at his feet.

New Zealand’s Land Wars

But invasion and war in the Waikato in 1863 would force the Māori King Tawhiao into refuge, deep in Ngāti Maniapoto country, where he would remain for a generation, refusing Crown overtures, insisting on redress and justice for his people. But the spirit of Manawapou – Māori political unity – had not died. Māori continued to be ‘affronted and frustrated’ by their attempts to engage with the government, ‘disillusioned by the sham equality they had been offered’, writes historian Alan Ward.

But invasion and war in the Waikato in 1863 would force the Māori King Tawhiao into refuge, deep in Ngāti Maniapoto country, where he would remain for a generation, refusing Crown overtures, insisting on redress and justice for his people. But the spirit of Manawapou – Māori political unity – had not died. Māori continued to be ‘affronted and frustrated’ by their attempts to engage with the government, ‘disillusioned by the sham equality they had been offered’, writes historian Alan Ward.

In March 1881, an ‘Orākei Parliament’ was convened by Pāora Tūhaere of Ngāti Whātua, attended by 100 rangatira from throughout Aotearoa. Momentum gathered quickly, with hui convened at Waiapu, Waiomatatini, Omāhau and Putiki Pā, Whanganui. Perhaps appropriately, it was Te Tiriti o Waitangi Marae, Waitangi, which hosted the establishment of Te Kotahitanga, or Parematta Māori (Māori Parliament) on 14 April 1892.

By one count, 1342 rangatira from all over Aotearoa attended. This inaugural hui was convened by Heta Te Haara of Ngāpuhi, assisted by Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui from Whanganui who would later convene a Kotahitanga committee to determine all structural and electoral issues. Further hui were convened throughout the country, with a Speaker and Prime Minister appointed, along with rules and protocols to govern proceedings. Ministers were also appointed, including a Minister of Pākeha Affairs. Māori women were eventually admitted as members and given speaking rights, long before women were admitted to the Pākehā Parliament.

The problem, however, was continuing government hostility. Attempts to have Parematta Māori conferred with a measure of autonomy failed. In the end, the urgency to deal with egregious land loss, and the wretched condition of pā and papa kāinga, forced Kotahitanga leaders to compromise with the Liberal government. In 1900, Māori leaders agreed to an alternative network of goverment-sponsored land and health committees, following promises of inherent rangatiratanga. The new network brought Te Kotahitanga to an end.

The end of Te Kotahitanga

Within five years, the network was being dismantled. Attempts to revive Te Kotahitanga failed. By the First World War, Māori conceded that they needed to work ‘within the system’. They had little choice, argues historian Richard Hill, with pā and papa kāinga now facing desolation and penury, exacerbated by massive land losses and devastated tribal economies. And there is has remained, with Māori working ‘within the system’, as they do today.

![19 Māori Trust Boards were established between 1922 (Te Arawa) and 1991 (Orākei) as an imperfect means of co-governance between Māori and the Crown. Image is cover of forthcoming book 'A History of the Māori Trust Boards 1922-2022' by Danny Keenan, to be released in 2025 [date yet to be determined].](https://newzealandwars.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Trust-Bds-book-cover-2023-259x300.png) Over time, some concessions were made to iwi through the Māori Trust Boards, with 19 set up between 1922 and 1991 as a limited means of restoring economies and resolving historical claims. Limited degrees of power and resources were transferred direct to iwi groups. Post-Treaty settlements led to the conversion of most Boards into new independent governing entities with powers still confined to tribal economies. *

Over time, some concessions were made to iwi through the Māori Trust Boards, with 19 set up between 1922 and 1991 as a limited means of restoring economies and resolving historical claims. Limited degrees of power and resources were transferred direct to iwi groups. Post-Treaty settlements led to the conversion of most Boards into new independent governing entities with powers still confined to tribal economies. *

But governments were ambivalent, hostile to the Boards’ limited powers, insisting that Māori were benefitting anyway from generic welfare policies. We heard this from welfarist governments in the 1930s. We hear it today from the current hard-man government. Hostility to Māori political autonomy, grounded in Pākehā insecurity, has been with us for a long time.

The ethos of ‘pan-tribal’ also emerged, exemplified by the growth of the Ratana Movement after 1918 and the rise of pan-tribal entities like the Māori Women’s Welfare league in 1951, the New Zealand Māori Council in 1962 and the Mana Motuhake Party in the later 1970s, arguably the forerunner of Te Pāti Māori today. But Māori aspirations for political autonomy have occasionally resurfaced, like the National Māori Congress formed at Turangawaewae Marae in July 1990.

But the intent was limited. The Congress claimed no powers over tribal resources or negotiations. Instead, as enunciated by Mason Durie at the time, the Congress would advance the political interests of all Māori, uniting the tribes in their continuing search for economic regeneration, cultural revitalization, and, not least, te tino rangatiratanga.

Moves, then, to establish an autonomous Māori presence, much less a Māori Parliament, haven’t fared well. Could a Parematta Māori arise again?

A modern Te Kotahitanga / Māori Parliament?

In earlier times, Māori petitioned for autonomy in order to challenge – and take control of – wholesale depletion of customary lands, iniquitous legislation, political inequality and economic marginalization, all exacerbated by population losses and wretched community conditions. Rangatira assembled far and wide in their thousands, facing these egregious issues, providing leadership, and compelling attention.

Today, comparable issues remain for Māori, reframed for a different time. Whānau are still afflicted by negative statistics in health, education, income levels, housing and imprisonment, alongside less obvious measures like asset ownership, blue-collar concentration and suburban isolation with impoverished access to essential services like medicine and transport.

Today, comparable issues remain for Māori, reframed for a different time. Whānau are still afflicted by negative statistics in health, education, income levels, housing and imprisonment, alongside less obvious measures like asset ownership, blue-collar concentration and suburban isolation with impoverished access to essential services like medicine and transport.

There is no doubt that Te Pāti Māori leaders today reflect the determination of rangatira who in days gone by pressed so hard for Māori political independence. The issues are certainly there, with meaningful Māori-sourced remedies still obstructed by continuing government hostility. And the meddling is far from over – a Māori Health Authority abolished, te reo devalued, Treaty principles to be reframed to suit Crown purposes.

It’s a different world, of course. Māori have been working ‘inside the system’ for a long time. But Māori MPs of the 1890s like Hone Heke Ngāpua of Ngā Puhi, Hirini Taiwhanga of Ngā Puhi and Wiremu Parata of Ngāti Toa were also staunch supporters of an independent Parliament, providing the necessary vision and leadership that gave rise to the mass Māori Kotahitanga movement which set up the first Māori Parliament.

Such is the challenge that awaits Te Pāti Māori. However, with such rangatira and tūpuna standing behind her, espousing theologies of legitimation and liberation as they did, Debbie Packer-Ngawera is right to emphasize the role an independent Māori polity can play in ‘transforming of Aotearoa’ into a nation which respects the te tino rangatiratanga of all peoples.

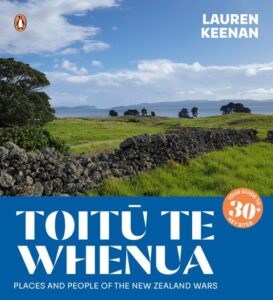

![The Lockwood Flag, with black above silver fern [the other one had red] - a flag rejected by New Zealanders who preferred the Union Jack on our flag, instead of the silver fern.](https://newzealandwars.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/flag-300x141.jpg) FURTHER READING: Danny Keenan, Fate of the Land. Ko Ngā Ākinga a ngā Rangatira. Māori Political Struggle in the Liberal Era 1891-1912, Massey University Press, Auckland, 2023, pp. 138-155; Maria Bargh (ed), Māori and Parliament: Diverse Strategies and Compromises, Huia Publishers, Wellington, 2010.

FURTHER READING: Danny Keenan, Fate of the Land. Ko Ngā Ākinga a ngā Rangatira. Māori Political Struggle in the Liberal Era 1891-1912, Massey University Press, Auckland, 2023, pp. 138-155; Maria Bargh (ed), Māori and Parliament: Diverse Strategies and Compromises, Huia Publishers, Wellington, 2010.

- * If you would like to know more about the Māori Trust Boards, and the book writing project commissioned by Minister Mahuta and Te Puni Kokiri, see here – Māori Trust Boards.