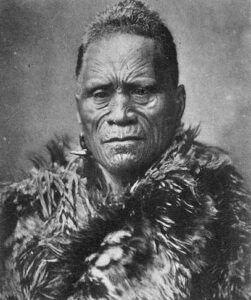

Where King Tawhiao carried a ‘terrible burden’ for all Māori

New Zealand’s Land Wars were lost by Māori in the Waikato, in 1863. Here is an extract from an essay Danny Keenan published in 2001, arguing that, for Māori, the critical battle was fought at Rangiriri in November, 1863. The focus of the essay, published in the Mana Magazine, is King Tawhiao, appointed Māori King in 1860.

New Zealand’s Land Wars were lost by Māori in the Waikato, in 1863. Here is an extract from an essay Danny Keenan published in 2001, arguing that, for Māori, the critical battle was fought at Rangiriri in November, 1863. The focus of the essay, published in the Mana Magazine, is King Tawhiao, appointed Māori King in 1860.

![]() “The most significant battle of the war was at Rangiriri on November 20, 1863. On that day, [King] Tawhiao and his Tainui people carried a terrible burden for all Māori. It was here that it was decided who would control New Zealand – Māori or Pākehā. For Māori to have at least some vestige of control over Aotearoa, Tawhiao’s warriors needed either to beat the British Forces, or inflict enought damage on them to force conessions.

“The most significant battle of the war was at Rangiriri on November 20, 1863. On that day, [King] Tawhiao and his Tainui people carried a terrible burden for all Māori. It was here that it was decided who would control New Zealand – Māori or Pākehā. For Māori to have at least some vestige of control over Aotearoa, Tawhiao’s warriors needed either to beat the British Forces, or inflict enought damage on them to force conessions.

They did neither. And on December 8 1863 General Cameron entered Ngāruawahia and ran up the Union Jack over Tawhiao’s home.”

Invasion of the Waikato

12 July 1863 Commander of British Army, Lieutenant General Duncan Cameron, ordered a force of Regulars to march out from Queen’s Redoubt at Pukeno and, marching south, to cross the Managatawhiri Stream and into the Waikato, beginning the invasion of the Waikato.

12 July 1863 Commander of British Army, Lieutenant General Duncan Cameron, ordered a force of Regulars to march out from Queen’s Redoubt at Pukeno and, marching south, to cross the Managatawhiri Stream and into the Waikato, beginning the invasion of the Waikato.

17 July 1863 British Army encountered Māori on Koheroa Ridge and at Martin’s Farm, with six Regulars killed and thirty three injured. Thirty Māori also died at Koheroa.

22 July – 14 September 1863 Invading British engaged in skirmishes with Māori at Kirikiri, Pokeno, Camerontown, Kakaramea and Pukekohe East. Some of these encounters involved Māori moving north of the Mangatawhiri Stream and attacking the flanks of the British Army.

30 October 1863 The huge hilltop fortress of Meremere is shelled by two British Army gunboats, compelling Māori to withdraw after an initial resistance.

20 November 1863 The British Army attacked Rangiriri fortress with an initial force of 850 naval officers and men, engineers, artillery and infantry regulars. Frontal assaults fail to dislodge the determined defenders. Darkness fell over the inconclusive battlefield. During the night, most Māori withdrew south, slipping through the British Army cordon. Among those who escaped was the Māori King, – Tawhiao.

21 November 1863 At daybreak, Māori hoist the white flag. British Army officers entered the Pā to negotiate a Māori surrender. 183 Māori captives were sent to Auckland. A large force of Māori, approaching from Paetāhi to the south, withdrew upon learning of the surrender. The death toll at Rangiriri was particularly high – 47 British Regulars killed with 85 wounded. Fifty Māori also died at Rangiriri.

For an account of the significance of this engagement at Rangiriri, see Battle of Rangiriri, where Māori lost their country.

8 December 1863 The British Army entered the Māori King’s papakāinga (home) at Ngāruawāhia unopposed. King Tāwhiao, retreated further south.

9 December 1863 Union Jack hoisted over Māori King’s house, now used to store supplies.

21 February 1864 Surprise attack by British Army on the ‘foodbasket of the Waikato’, the village of Rangiaowhia, destroying village and surrounding cultivations. Thereafter, British Army pursued Māori as they fell back, with a major skirmish fought at Hairini resulting in twenty five Māori deaths.

31 March – 2 April 1864 ‘Rewi’s Last Stand’ occured at Orakau when Rewi Maniapoto and allies faced the oncoming British Army from within the Pā at Orakau. After intense fighting and a two day siege, Rewi’s people attempted a breakout with tragic results. Highest single day’s Māori death toll with 160 killed and 50 wounded. Seventeen British Regulars also died with 51 wounded. The Battle of Orakau brought the Waikato campaign to an end.

To read Danny’s essay on King Tawhiao, as published in the Mana Magazine, No 40, 2001, pp. 78-79, see King Tawhiao.

Also, to read Danny’s essay on the history of the King Movement, as published in the Mana Magazine, No 50, 2003, pp.63-68, see History of Kingitanga.

To see a map of the Waikato conflicts, alongside the other fields of engagement that together comprised the ‘New Zealand Wars’, see Map of Conflicts.