A new Māori Queen has been appointed

Ngā Wai Hono i Te Po Paki has been appointed as the new Māori monarch, to replace her father, King Tūheita who passed away recently. Queen Ngā Wai Hono I Te Po is aged 27; and is the youngest daughter of King Tūheita.

Ngā Wai Hono i Te Po Paki has been appointed as the new Māori monarch, to replace her father, King Tūheita who passed away recently. Queen Ngā Wai Hono I Te Po is aged 27; and is the youngest daughter of King Tūheita.

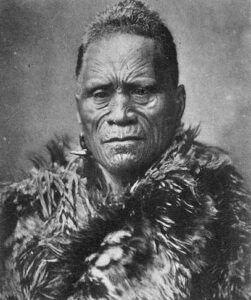

Māori King Tuheita 1955-2024

The sad news that Māori King Tūheita Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII has passed away reminds us again of the tragic yet important history of the Kingitanga.

The sad news that Māori King Tūheita Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII has passed away reminds us again of the tragic yet important history of the Kingitanga.

Established at Rangiriri in 1858, the Kingitanga united all Maori against the colonial encroachment of unforgiving settlers and the Crown. In 1863, the second King, King Tawhiao, bore a terrible burden for all Māori when he and his Tainui people faced down the British Army which, at the Crown’s bidding, invaded the Waikato [see below].

Established at Rangiriri in 1858, the Kingitanga united all Maori against the colonial encroachment of unforgiving settlers and the Crown. In 1863, the second King, King Tawhiao, bore a terrible burden for all Māori when he and his Tainui people faced down the British Army which, at the Crown’s bidding, invaded the Waikato [see below].

The wars effectively ended for Māori on 20-21 November 1863 at the battle of Rangiriri, though fighting would continue all over the North Island for another ten years.

At Rangiriri, Tawhaio needed to either defeat the British, or inflict enough damage to force terms. He was able to do neither. Instead, King Tawhiao was forced into a long retreat that ended with his taking refuge for a generation within Ngāti Maniapoto, near Te Kuiti. King Tawhiao sadly died in 1892. But this was not the end of the Kingitanga, far from it, as all Kingitanga successors would abundantly demonstrate, not least King Tuheita.

You can read about the history of the Kingitanga here – the Māori King.

This essay on the Kingitanga was published in 2003 in the Mana Magazine in order to celebrate the life and achievements of the Māori Queen, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangi Kaahu, who was King Tuheita’s mother. Te Arikinui sadly passed away in 2006.

SOURCES An excellent source on the Kingitanga is Angella Ballara (ed), Te Kīngitanga. The People of the Māori King Movement, published by The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography / Auckland University Press, Auckland, 1996. Another excellent source is an article written by noted New Zealand historian MPK Sorrenson – ‘The Maori King Movement’ in MPK Sorrenson, Ko Te Whenua Te Utu – Land is the Price, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2014, pp. 106-125. The origins and history of the Kingitanga between 1855 and 1912 are also described, within the complex context of turbulent political challenge faced by all Māori, in Danny Keenan, The Fate of the Land Ko Ngā Ākinga a nga Rangatira. Māori Political Struggle in the Liberal Era 1891-1912, Massey University Press, Auckland, 2023.

Paepae as controlling site of memory

The paepae is the place on the marae where elders stand to deliver their speeches and, as it so happens, to present their memories – or versions of history. The paepae provides context and legitimacy for the histories – and memories – that follow.

The paepae is the place on the marae where elders stand to deliver their speeches and, as it so happens, to present their memories – or versions of history. The paepae provides context and legitimacy for the histories – and memories – that follow.

The paepae, then, can be said to be the controlling site of all Māori knowledge, including knowledge of the past. Speeches are an oral process of course, delivered before a discriminating audience of elders and whānau. For Māori, such whaikōrero facilitates many things, not least the art of remembering.

Who is forgetting the NZ Wars ..? – it’s not Māori

In the context of the New Zealand Wars, it is often said by Pākehā historians that ‘we have forgotten the wars’. Whilst this might be true of Pākehā, it is not true for Māori.

‘Forgetting the wars’ is a conversation Pākehā are having with themselves; it does not involve Māori. Pākehā historians don’t make this clear, but they should. Māori have never forgotten the wars. Danny had an article on this matter published in a number of newspapers early in 2022 – you can read the article here – Māori have not forgotten the wars.

Pākehā historians are also now widely promoting the view that the New Zealand Wars were decided in the Waikato, failing to acknowledge the historiography surrounding such views. Perhaps this might be because Māori historians have been arguing [and publishing] this same view for over twenty years.

Here is an essay published in the Mana Magazine in 2001 dealing with King Tawhiao of the Kingitanga, and the ‘terrible burder he carried for all Māori’ especially at the battle of Rangiriri on 20 November 1863. As mentioned above, in order to retain any vestige of control over Aotearoa, Tawhiao had to defeat the British Army at Rangiri, or at least inflict enough damage to force terms. His warriors were able to do neither, with the British pouring through and capturing Ngāruawahia, where the Union Jack was hoisted over KIng Tawhiao’s home, on 6 December 1863.

Here is an essay published in the Mana Magazine in 2001 dealing with King Tawhiao of the Kingitanga, and the ‘terrible burder he carried for all Māori’ especially at the battle of Rangiriri on 20 November 1863. As mentioned above, in order to retain any vestige of control over Aotearoa, Tawhiao had to defeat the British Army at Rangiri, or at least inflict enough damage to force terms. His warriors were able to do neither, with the British pouring through and capturing Ngāruawahia, where the Union Jack was hoisted over KIng Tawhiao’s home, on 6 December 1863.

These are the stories and memories that are not forgotten by Māori.

How then do kaumātua bring to mind such memories, histories and knowledge when delivering oratory from the paepae? If we think about this process – that of a cultural retention of memory – we can see how deeply embedded such histories of trauma can be.

Compiling Oral Histories

During the 1990s, the compiling and writing of oral histories became a particular interest of Māori who were then setting out as ‘historians’, whether as Māori historians or tribal historians.

The distinction wasn’t important to Māori, since methods and processes were largely the same for both groups. However, a small group of Māori historians working within mainstream universities, and disciplines, did emerge, eventually establishing Te Pouhere Korero, a network of Māori historians. This gave rise to a small but interesting literature, written by Māori, focusing on what exactly oral history was to Māori – its methods, processes, protocols and value.

The distinction wasn’t important to Māori, since methods and processes were largely the same for both groups. However, a small group of Māori historians working within mainstream universities, and disciplines, did emerge, eventually establishing Te Pouhere Korero, a network of Māori historians. This gave rise to a small but interesting literature, written by Māori, focusing on what exactly oral history was to Māori – its methods, processes, protocols and value.

Some attempt was also made, at this time, to locate those observations within a much broader mainstream literature dealing with oral history.

In 2005, Danny published an article on Māori oral history, ‘The Past From the Paepae’, where he argued that the form and frameworks of oral history for Māori took their cue from the paepae.

That is, from the place where elders stood, when delivering important speeches, especially to visitors coming onto the marae (the marae of course being the temporal, living embodiment of all Māori knowledge, including knowledge 0f the past, or history).

To read the article – The Past from the Paepae. The reference is – Danny Keenan, ‘The Past from the Paepae. The Uses of the Past in Māori History’ in Māori Oral History: A Collection, (eds) Rachel Selby and Alison Laurie, Oral History Association of New Zealand, Wellington, pp. 54-61 [see cover above, left].

For a discussion of how Māori histories might intersect with Pākehā histories, see Danny Keenan, Mā Pango, Mā Whero, Ka Oti, Unities and Fragments in Māori History, in Bronwyn Dalley and Bronwyn Labrum (eds), Fragments. New Zealand Social and Cultural History, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2000, pp. 39-53.

For a discussion of how Māori histories might intersect with Pākehā histories, see Danny Keenan, Mā Pango, Mā Whero, Ka Oti, Unities and Fragments in Māori History, in Bronwyn Dalley and Bronwyn Labrum (eds), Fragments. New Zealand Social and Cultural History, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2000, pp. 39-53.